1. Science fiction, above all a prospective form of fiction, concerned with the immediate present in terms of the future rather than the past, requires narrative techniques that reflect its subject matter. To date almost all its writers, including myself, fall to the ground because they fail to realise that the principal narrative technique of retrospective fiction, the sequential and consequential narrative, based as it is on an already established set of events and relationships, is wholly unsuited to create the images of a future that has as yet made no concessions to us. In The Drowned World, The Drought and The Crystal World I tried to construct linear systems that made no use of the sequential elements of time — basically, a handful of ontological “myths”. However, in spite of my efforts, the landscapes of these novels more and more began to quantify themselves. Images and events became isolated, defining their own boundaries. Crocodiles enthroned themselves in the armour of their own tissues.

2. In The Terminal Beach the elements of sequential narrative had been almost completely eliminated. it occurred to me that one could carry this to its logical conclusion, and a recent group of stories — You and Me and the Continuum, The Assassination Weapon, You: Coma: Marilyn Monroe and The Atrocity Exhibition –– show some of the results. Apart from anything else, this new narrative technique seems to show a tremendous gain in the density of ideas and images. In fact, I regard each of them as a complete novel.

3. Who else is trying? Here and there, one or two. More power to their elbows. But for all the talk, most of the established writers seem stuck in a rut.

4. Few of them bad much of a chance, anyway: not enough wild genes…

5. Of those I have read, Platt’s Lone Zone (in particular, the first three or four paragraphs, briiliant writing) and Colvin’s The Pleasure Garden … and The Ruins are wholly original attempts, successful I feel, to enlarge the scope and subject matter of science fiction.

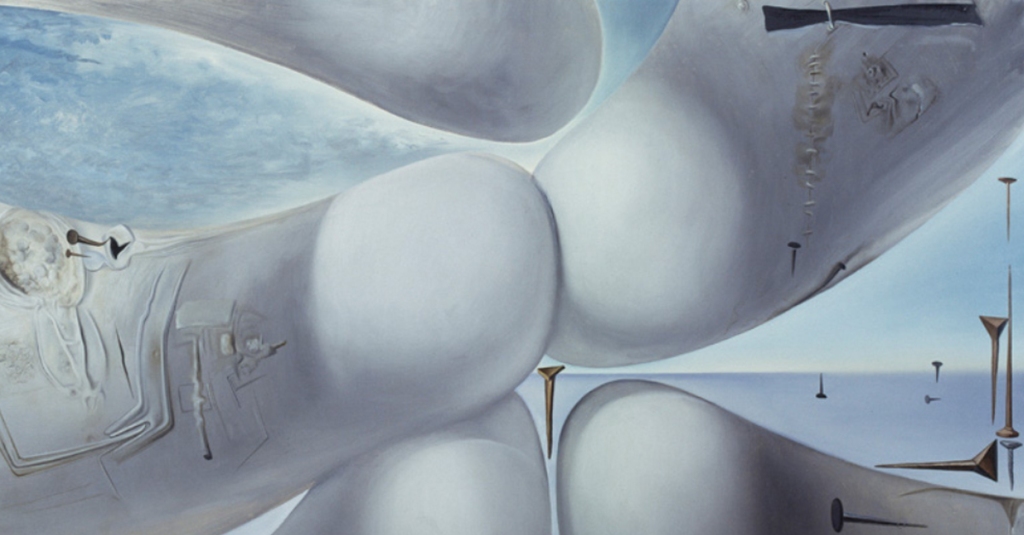

6. Defend Dali.

7. In fact, the revival of interest in surrealism –after the recent flurry over Dada, there is now a full-scale retrospective of Duchamp at the Tate Gallery — bodes well for science fiction, turning its writers away frorn so-called realism to a more open and imaginative manner. One hopes that its real aims will be followed. One trouble with Dali is that no one has ever really looked at his paintings. “Goddess leaning on her elbow,” for example, or “Young Virgin auto-sodomised by her own chastity,” seem to me to be among the most important paintings of the 20th century.

8. The social novel is dead. Like all retrospective fiction, it is obsessed with the past, with the roots’ of behaviour and background, with sins of omission and commission long-past, with all the distant antecedents of the present. Most people, thank God, have declared a moratorium on the past, and are more concerned with the present and future, with all the possibilities of their lives. To begin with: the possibilities of musculature and posture, the time and space of our immediate physical environments.

9. Fiction is a branch of neurology.

10. Planes intersect: on one level, the world of public events, Cape Kennedy and Viet Nam mimetised on billboards. On another level, the immediate personal environment, the volumes of space enclosed by my opposed hands, the geometry of my own postures, the time-values contained in this room, the motion-space of highways, staircases, the angles between these walls. On a third level, the inner world of the psyche. Where these planes intersect, images are born. With these co-ordinates, some kind of valid reality begins to clarify itself.

11. Quantify.

12. Some of these ideas can be seen in my four recent “novels”. The linear elements have been eliminated, the reality of the narrative is relativistic. Therefore place on the events only the perspective of a given instant, a given set of images and relationships.

13. Dali: “After Freud’s explorations within the psyche it is now the outer world of reality which will have to be quantified and eroticised.” Query: at what point does the plane of intersection of two cones become sexually more stimulating than Elizabeth Taylor’s cleavage?

14. Neurology is a branch of fiction: the scenarios of nerve and blood-vessel are the written mythologies of brain and body. Does the angle between two walls have a happy ending?

15. Query: does the plane of intersection of the body of this woman in my room with the cleavage of Elizabeth Taylor generate a valid image of the glazed eyes of Chiang Kai Shek, an invasion plan of the offshore islands?

16. Of course these four published “novels”, and those that I am working on now, contain a number of other ideas. However, one can distinguish between the manifest content, ie., the attempt to produce a new “mythology” out of the intersecting identities of J. F. Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, smashed automobiles and dead apartments, and the latent content, the shift in geometric formula from one chapter to the next. Each section is a symbol in some kind of spinal mathematics. In fact I believe that one may be able one day to represent a novel or short story, with all its images and relationships, simply as a three-dimensional geometric model. In The Atrocity Exhibition one of the characters remarks of a set of Enneper’s models “. . . operating formulae, for a doomsday weapon.” Cubism, for example, had a greater destructive power than all the explosives discharged during World War I — and killed no one.

17. The analytic function of this new fiction should not be overlooked. Most fiction is synthetic in method — as Freud remarked, rightly I feel, a sure sign of immaturity.

18. Au revoir, jewelled alligators and white hotels, hallucinatory forests, farewell.

19. For the moment it’s difficult to tell where this thing will go. One problem that worries me is that a short story, or even, ultimately, a novel, may become nothing more than a three-dimensional geometric model. Nevertheless, it seems to me that so much of what is going on, on both sides of the retina, makes nonsense unless viewed in these terms. A huge portion of our lives is ignored, merely because it plays no direct part in conscious experience.

20. No one in science fiction has ever written about outer space. You and Me and the Continuum: “What is space?” the lecturer concluded, “what does it mean to our sense of time and the images we carry of our finite lives … ?” At present I am working on a story about a disaster in space which, however badly, makes a first attempt to describe what space means. So far, science fiction’s idea of outer space has resembled a fish’s image of life on land as a goldfish bowl.

21. The surrealist painter, Matta: “Why must we await, and fear, a disaster in space in order to understand our own times?”

22. In my own story a disaster in space is translated into the terms of our own inner and outer environments. It may be that certain interesting ideas will emerge.

23. So far, science fiction has demonstrated conclusively that it has no idea of what space means, and is completely unequipped to describe what will no doubt be the greatest transformation of the life of this planet — the exploration of outer space.

24. Meanwhile: the prospect of a journey to Spain, a return to the drained basin of the Rio Seco. At the mouth a delta of shingle forms an ocean bar, pools of warm water filled with sea-urchins. Then the great deck of the drained river running inland, crossed by the white span of a modern motor bridge. Beyond this, secret basins of cracked mud the size of ballrooms, models of a state of mind, a curvilinear labyrinth. The limitless neural geometry of the landscape. The apartment houses on the beach are the operating formulae for our passage through consciousness. To the north a shoulder of Pre-Cambrian rock rises from the sea after its crossing from Africa. The juke-boxes play in the bars of Benidorm. The molten sea swallows the shadow of the Guardia Civil helicopter.

J. G. Ballard. “Notes from Nowhere: Comments on Work in Progress.” New Worlds. October, 1966. (Michael Moorcock writes, “Reader interest in J. G. Ballard’s recent work has been high. We invited Mr. Ballard to produce these notes explaining some of his current ideas. They take the form of a dialogue with himself – the answers explaining the unstated questions.”)

Leave a comment